Nightlife And The Evening Economy: Aaditya Thackeray Seems To Have Understood It Well, When Will Others Follow Suit

Yuva Sena President Aaditya Thackeray last week (20 December) tweeted out that state government (of which the Shiv Sena is a part) had notified a proposal titled ‘Mumbai 24 hours’. The proposal in question, spearheaded by the junior Thackeray seeks to allow businesses to stay open 24 hours.

Often 24 hour cafés are in 5 star hotels but the ones I’ve proposed are in non residential areas, malls, mill compounds- accessible to the common man. Leisure time for hard working Mumbaikars is a must

— Aaditya Thackeray (@AUThackeray) December 20, 2017

N

Now it is worth noting that Thackeray mentions establishments outside of five-star hotels in non-residential areas that can be accessed by all and sundry. This seems to be a good move to ensure that nightlife in the country’s financial capital is given its due, since most establishments down their shutters by 2 am.

Why is nightlife important?

The ‘regular’ society usually goes to sleep at night and wakes up the next morning to continue their life. However, with the advent of globalism, world is fast-changing to adapt to 24-hour activity. Take the example of the information technology (IT) and the IT-enabled services (ITES) sectors. Both of them – predominantly dealing with clients in the west – are pretty much active the entire day. Even the media, today functions round-the-clock. Freelancers across various industries too are active across the day, not just to deliver to foreign clients, but also within the country.

With establishments being active throughout the day and night, it gives people an opportunity to venture out at night for various reasons. Many a café that offers internet connectivity attracts people looking to get work done.

Mumbai, like most other metropolitan areas in India is home to numerous startups. Startups, by virtue of being startups invariably see a flexible work schedule usually running beyond the confines of sunlight.

Many such entities operate out of cafes and other establishments (including shared workspaces) due to the lack of a physical office and would thus be the biggest beneficiary of such a move. They could now hold meetings, meet people or just get some work down outside of their usual spaces.

A shift in a city’s operations

Night-time has hitherto been the domain of young partygoers. Work usually takes a backseat, but off-late it has seen an increased presence in major cities.

This brings about another important factor: Crime. A lot of crimes take place at night when fewer people are out. If more people venture out, it would in essence make it more difficult for criminals to strike. This sends out an important point to the law enforcement: Increase patrolling at night. However, in a country like India, it might see an increase in moral policing as well.

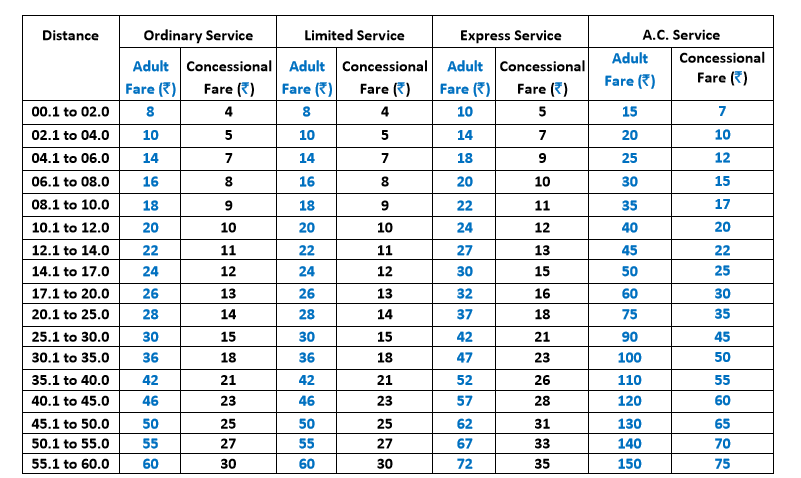

The next logical step for the administration is to increase the availability of public transport at night. With the advent of ride-sharing, traveling at night is an easier affair, but then ride-sharing is not everyone’s cup of tea. More buses and trains in the night will mean people who stay out late or have to leave in the dead of the night will have transit options, thus leading to better productivity in terms of real-time activity.

However, nightlife does come with a rider – those who venture out at night must accept that they face the risk of being the victims of a crime. Conversely, it also indicates that law enforcement must step up to ensure better vigilance and patrol at night.

While Mumbai doesn’t have a sizable amount of industries that operate throughout the clock-cycle, other cities such as nearby Pune and Bengaluru do. For many an IT employee, working the night shift usually means the lack of access to a restaurant or café in the event they want to go out. Shouldn’t they too have the freedom to go to an establishment at any time of the day?

Thackeray, being a youngster, clearly understands the advantages of having a continuously operating city. Perhaps it is time that other cities too, take a look at it.

Now for the transit

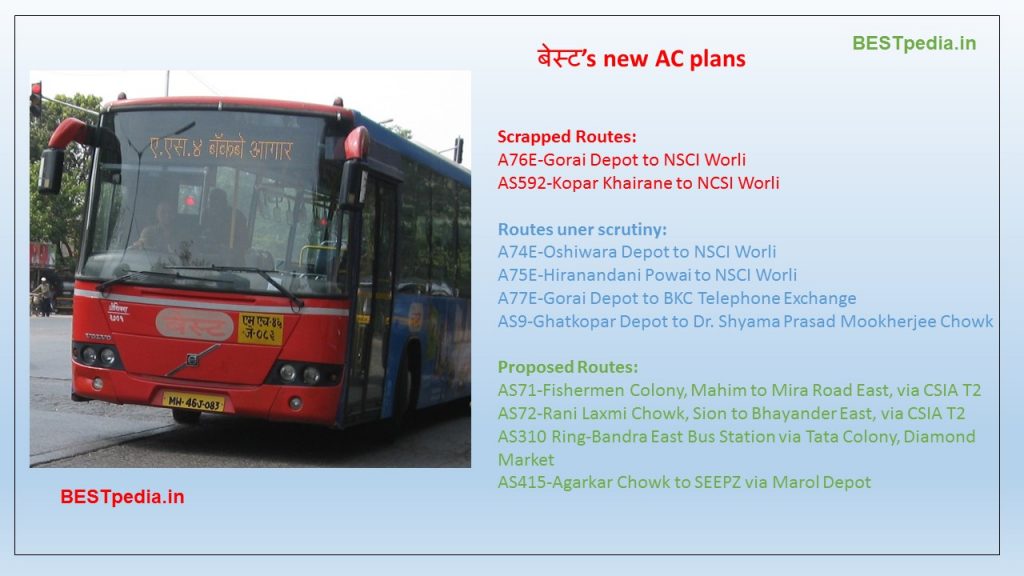

It is imperative that public transit remains functional all the time. The Suburban network shuts of for 2.5 hours in the night. The Metro shuts at midnight. Why not have them operational round the clock? Let buses run at night too, not just BEST, TMT and NMMT, but also MSRTC. The last Shivneri between Mumbai and Pune leaves at 11-11.30 in each direction. It needs to operate even at night, at least towards Mumbai.

Having any time transit is the first step to more economic activity and productivity.

![]()