In the recent past, one major change in how we commute is how ride-sharing platforms have changed their operations. Prior to the pandemic and lockdown, everything was online, digital and there was a lot of crying around. But now, the system has completely changed.

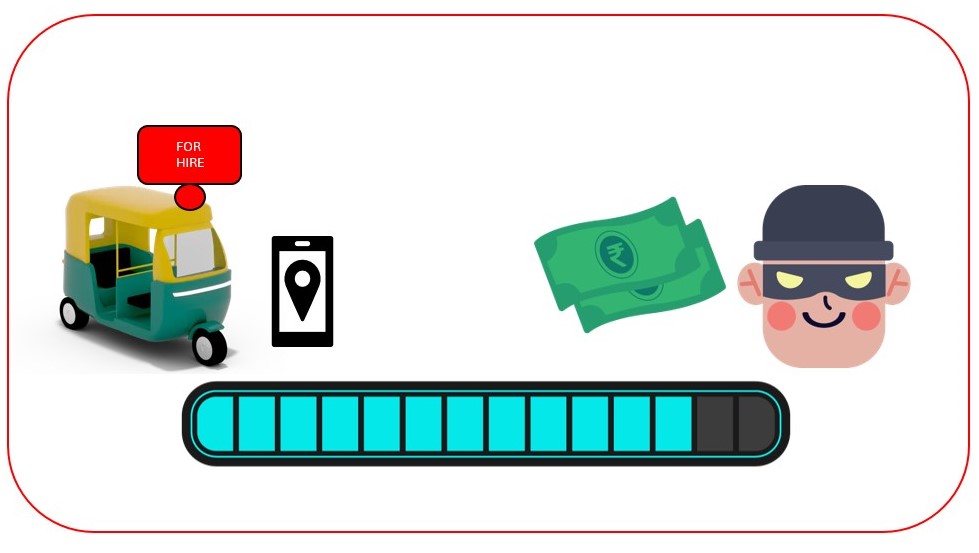

Let’s start with the most obvious change. You can no longer automatically pay for auto rides in most cities in India. You have to manually pay your driver at the end of the trip and more often than not, things don’t exactly go as per expected.

The story of protests against Uber and Ola over the contentious issue of commissions is not a new one. High commissions from the aggregators’ side have led to multiple instances of violence, with taxis being set on fire, offices and vandalised and even customers being harassed and abused. I’ve been at the receiving end of it myself, in 2017. You can read about it here: Bengaluru’s Uber, Ola Drivers’ Greed Has Led to Hooliganism on The Quint.

Then came Namma Yatri. And along with it, the guilt tripping. “WHY USE AN APP THAT CHARGES THIS MUCH COMMISSION WHEN YOU CAN USE AN APP THAT HAS ZERO COMMISSION?” is the standard argument all their ads have made. Remind me again who was involved in arson and violence? Not the commuter. Who gets guilt-tripped? The commuter. The person who pays for the service.

Now, NammaYatri is backed by JusPay, a payments processor. This is important because as a fintech firm, JusPay knows how much it costs to operate a ride-hailing service.

With aggregators moving away from the earlier model to basically acting as a connecting platform for drivers. In 2016, I had written that India is better off with Uber and Ola drivers being labelled as self-employed. You can read it here: India Is Better Off With Self-Employed Uber And Ola Drivers. In the article, I had argued that the ‘self-employed’ model of drivers was indeed the best model for cabdrivers as it gave them the flexibility to operate, which would be gone if they were to be classified as regular employees. My view has remained the same, albeit my stance on libertarianism has softened significantly, especially post the pandemic and consequent lockdowns. Remember I had once posted about a platform called ‘LibreTaxi’? Move Over Ola and Uber, LibreTaxi Is Here. My views on this have changed significantly.

Now, before I go into the main story, let me also drop another name here: ONDC and the Beckn protocol. The Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) is a Government of India-backed public technology initiative that was launched in 2021 to enable a level playing field for smaller players in the e-commerce field. It was meant to provide an open, inclusive system for retailers, shoppers, technology platforms and prevent cartelisation of the sector by Big Tech giants like Amazon, retail giants like Walmart (through Flipkart), and even our homegrown duopolies of Zomato and Swiggy. Eventually, it has evolved into an ecosystem that today also includes the transport sector (through Namma Yatri).

If you want to see how ONDC functions, simply open the Paytm app, and search for either ONDC Food or ONDC Shopping. You can then place an order directly with the restaurant, who will then dispatch the order via a delivery partner (Dunzo, ShadowFax or others) and you pay with the app itself. ONDC is also available through other apps such as PhonePe, but I’ve only used it on Paytm.

The Beckn protocol functions as the backbone of the ONDC ecosystem by treating each entity (discovery, booking, payment, delivery and fulfillment) as separate entities or micro-transactions. Do read What is the Beckn protocol – the backbone of ONDC? To get a full understanding of how things work. Note. I absolutely love ONDC. It has made things cheaper, especially food deliveries. But while ONDC acts similar to using an aggregator for purchases, ride-sharing is a different story.

Now, coming back to Ola, Uber, Rapido, Namma Yatri, and their new model of services.

For starters, under the old model of operations, there was some accountability. Auto-drivers, especially in Chennai, who have never operated by meter were beginning to get in line. However, in this new method of operation, the idea is ‘please discuss the fare with the driver’, or ‘negotiate the fare with the driver’, which essentially means, pay whatever the driver demands since we are no longer involved and in the event you get overcharged, then you can’t even go and claim a refund.

Rapido in fact tells you that the fare is not enough if nobody accepts the trip and starts nudging you towards increasing the fare. Namma Yatri too does something similar, except it calls it a tip. Ola meanwhile just says your fare will be between x and y, please discuss it with your driver and in my experience, they demand more than what the higher number is. Off-late, Rapido has extended this ‘tech-stortion’ to bikes as well. And on top of that, the captains demand ‘tips’.

Another important aspect is privacy. Yes, while drivers already had access to some data about you, such as your name where you are going and your phone number (kudos to Uber and Namma Yatri for masking my number), now they will also know which bank I use and my legal name.

Alternatively, there is the case where drivers flat out refuse to accept online payments and demand cash because they don’t want to use a bank account (Hint: It has to do with Income Tax). If you’re lucky, the driver won’t argue too much and may not abuse you.

One more important factor is time. With the earlier model of letting the app handle payments, all I had to do is get out of the vehicle and go on my way. With the direct payment model, that is problematic. My phone’s battery might be low, I may not have a stable internet connection, (both of these have happened to me) and the lamest excuse: The driver is waiting for the SMS to reach his phone. When I asked an Uber driver when he got paid (for in-app payments), he told me payments are processed daily, and he got paid at the end of a calendar day. I don’t see what the problem with that is. Most of the users are salaried employees who get their salary at the end of the month.

In the recent past, once this new model of operations became the norm, there have been many cases when autowalas have refused to accept a ride for a certain fare. For the commuter, the app suggests that they either bump up the price or offer an extra tip (depending on the app) in order to get drivers to accept the ride. This is basically going back to the old method of haggling over fare before settling down on what the driver wants.

Ridesharing was meant to bring in order into an otherwise unorderly sector, but it seems to have done the exact opposite. At the same time, governments have begun to look at autos as a perennial vote bank and therefore neither enforce meter rates nor penalise them for overcharging. Essentially, it’s the commuter who is left in the lurch.

What are your views on this? Do drop a note in the comments below.

Update: The practice of demanding extra upfront has not gone unnoticed. The Central Consumer Protection Authority (CCPA) took cognizance of the fact and sent a notice to Uber, then Ola and also Rapido and Namma Yatri. Minister for Consumer Affairs Pralhad Joshi called it ‘unethical’, ‘exploitative’ and an ‘unfair trade practice’. However, like always they first targeted Uber, which in the eyes of Indian regulators is always the “greedy, hungry, foreign capitalist” while going after the home-grown variants only after netizens pointed it out. The issue was created by the latter, rather than the former.

![]()