Celebrations in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) peaked on 8 October 2025, as the Mumbai Metro’s Aqua line’s last leg – Aarey JVLR to Cuffe Parade was made operational, along with the inauguration of the Navi Mumbai International Airport. But what accompanied these events was the launch of the Mumbai One App. The National Common Mobility Card (NCMC) by the same name was launched with the inauguration of the Metro Yellow and Red lines, while the mobile application was in development for a long time. The wait has finally come to an end as the application is rolled out for public use with periodic updates.

Features

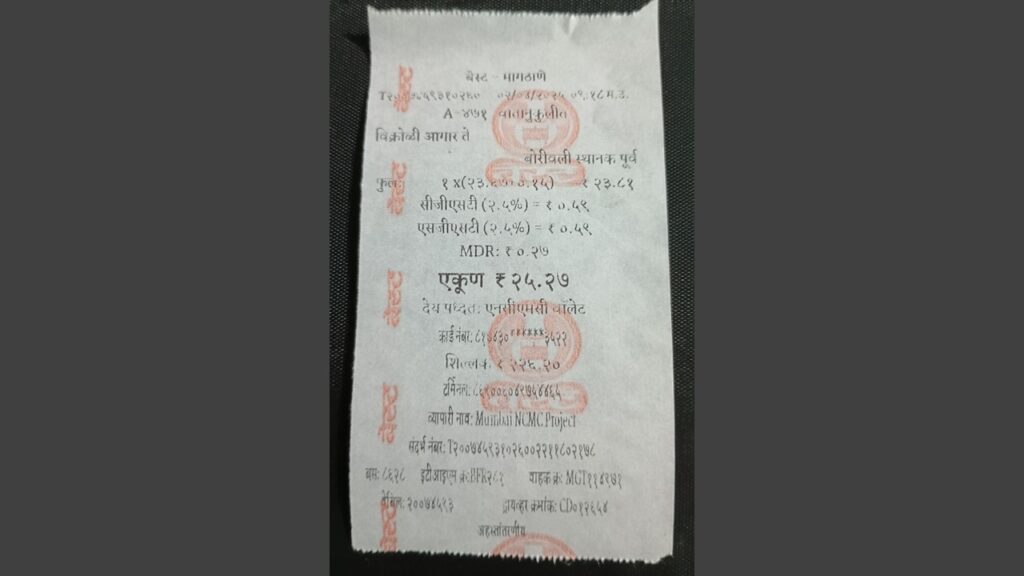

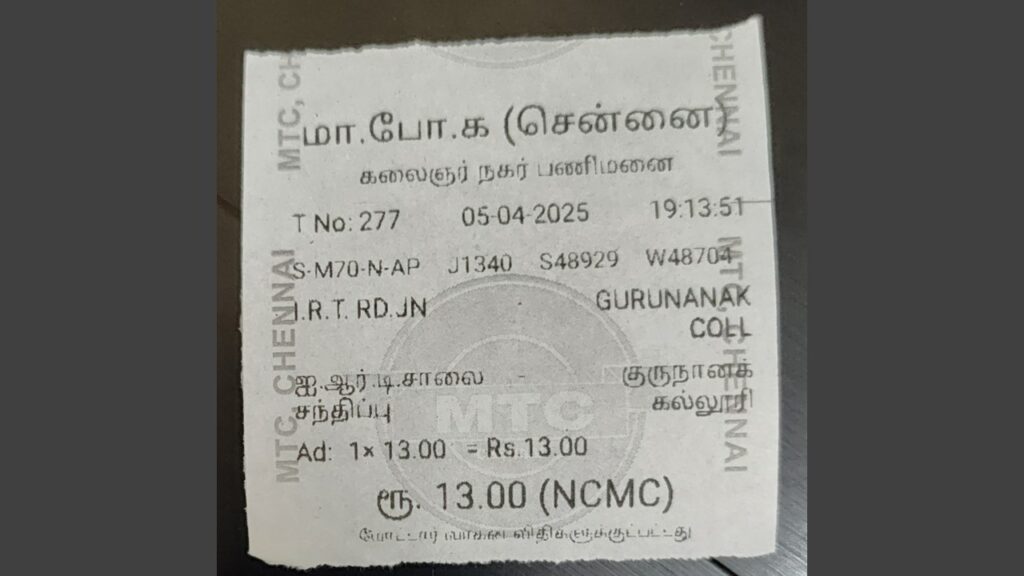

The Mumbai One app allows a passenger to travel across Mumbai City and its extended suburbs with a single payment system. This currently includes the Metro, Monorail, bus ticketing in BEST, NMMT, TMT and MBMT as well as the Mumbai Suburban Railway. The sole drawback of NCMC not being able to offer interoperability in other transport undertakings is ruled out as MMRDA has managed to bring buses, trains and metro ticketing under the ONDC umbrella. The app does not offer live tracking as of now, but the ticketing part is working well.

An interactive map – similar to the one seen at automatic ticket vending machines (ATVMs) at the railway stations is present in the app to choose the source and destination. Once finalised, the user can further filter out the mode of transport and choose which ticket to pay for.

A walkthrough video for the Mumbai One app can be seen below:

Metro and Suburban Rail

The Mumbai One app offers a quick ticketing feature for all the operational metro lines in Mumbai and Navi Mumbai, as well as the Mumbai Monorail. As Monorail services are suspended, it was not possible to test the app as of now. The Mumbai Metro Aqua line network was updated within 72 hours after the application was made available to the public. Suburban rail ticketing is linked with the UTS (Unreserved Ticketing System) App.

Bus Ticketing

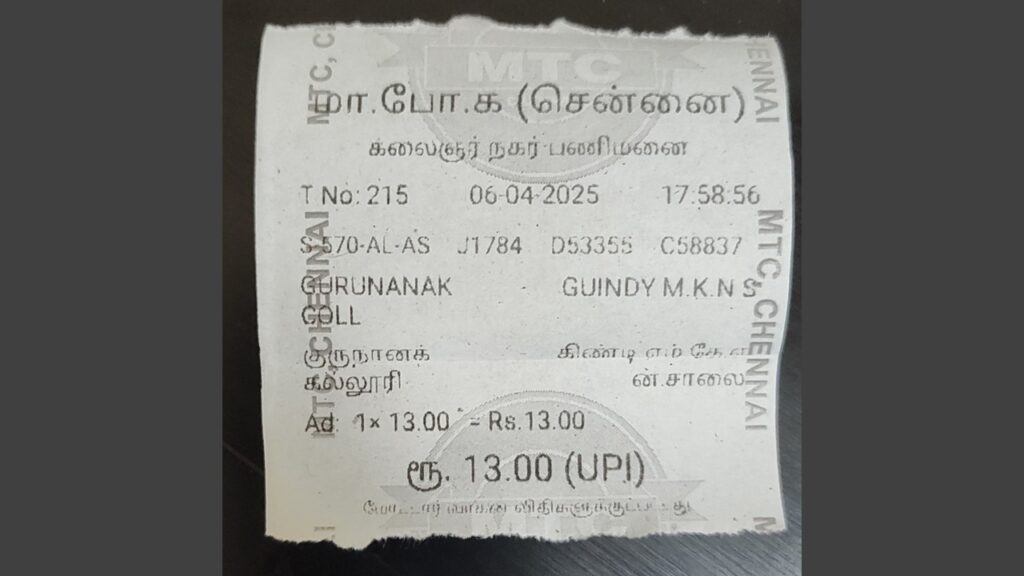

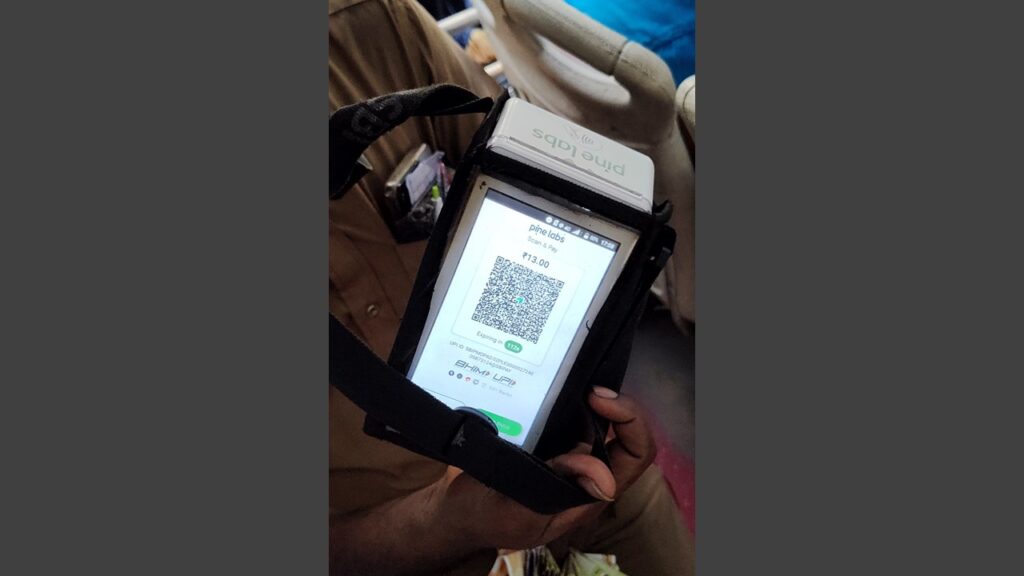

Travel on BEST buses was pretty simple, as the system for authenticating QR Tickets is already built into the Ticketing machines. Some conductors do confuse the ticket with a UPI Payment QR Code, but cooperate when made aware of the app.

Ground testing (not sponsored) took a month to bring the Thane Municipal Transport conductors aboard this system. TMT continued with ‘cash payment only’ until the complete rollout of the MaziTMT app this February. The system included two ways of verification – enabling the QR Code scanner in the ticketing machine or entering a token number, unique for each conductor. The conductors got so habituated to the token system, it became difficult to convince them to use the QR Code Scanner. In the earlier days, conductors complained of network errors in their machines as an excuse to deny e-ticketing, but that issue was resolved in a month once the higher-ups in TMT took cognisance of the same. The machines were updated within a week, and network connectivity is no more an excuse, and one can rely on the Mumbai One app as a mode of payment on board a TMT bus. Where a BEST conductor needs to feed stages and number of passengers before authenticating a mobile ticket, TMT went for a simpler system to just scan the M-Ticket QR and all the details easily flash in front of the conductor.

For NMMT and MBMT, the system is simple and sorted. The sole requirement is confirmation of the route from the bus conductor so as not to be confused with the short trips. Conductors happily guide the same, even in crowded situations. Ticket verification is done by simply opening the QR scanner on the ticketing machine. Both NMMT and MBMT have the same user interface for the ticketing system, which eliminates confusion. Both have a tie-up with PhonePe for digital payments and do not require entering any ticket details to verify mobile tickets purchased through the Mumbai One app.

Areas for Improvement

Ticketing in buses is a tedious part when dealing with digital payments, as the process takes an additional 30 seconds (every second counts), which creates a blocker for the conductor and inconvenience to the passengers. The Chalo app solved this with their in-app wallet and the Railways solved this issue with their R-Wallet linked to the UTS account. For some reason, one cannot book a return ticket for local trains through this app. There is a good scope to introduce an in-app wallet in Mumbai One, as Payments through the UPI Lite Wallet (a feature aimed at small payments without using UPI PIN) also take time to process by the payment gateway.

Conclusion

The Mumbai One application is solving the long-awaited problem of a common app to fulfil the travel needs in Mumbai & its extended suburbs. In future, we can expect all the errors sorted out at least in terms of bus ticketing. This article cannot be stretched more as the scenario is crystal clear, and users can happily rely on one app for travel needs in BEST, TMT, NMMT and MBMT. The next step towards a better commuting experience will be the integration of bus tracking with Google Maps. The railways are already on board, and so is BEST undertaking.

Download Mumbai One on Android and iOS.

P.S: BESTpedia is also on YouTube. Please do subscribe.

![]()