In what can only be considered a big boost for public transport, clean air and people’s pockets, the Cabinet approved the PM e-Bus Sewa on 16 August 2023.

Under this scheme, the Centre plans to deploy 10,000 electric buses across the country. According to the release on the Press Information Bureau, the buses will be deployed under the public-private partnership (PPP) model across 169 cities while the infrastructure will be upgraded in 181 cities under Green Urban Mobility Initiatives (GUMI). The estimated cost of the PM e-Bus Sewa is expected to be ₹57,613 crore and is expected to generate over 45,000 direct jobs.

All cities with a population above three lakh (as per the 2011 census) along with the capital cities of Union Territories, Northeastern region and the hill states will be covered with priority being given to those cities that currently do not have an organised bus service.

The programme is divided into two segments:

Segment A involves augmenting city bus services in 169 cities along with providing support for the associated infrastructure, upgradation of depots, establishment of substations, etc.

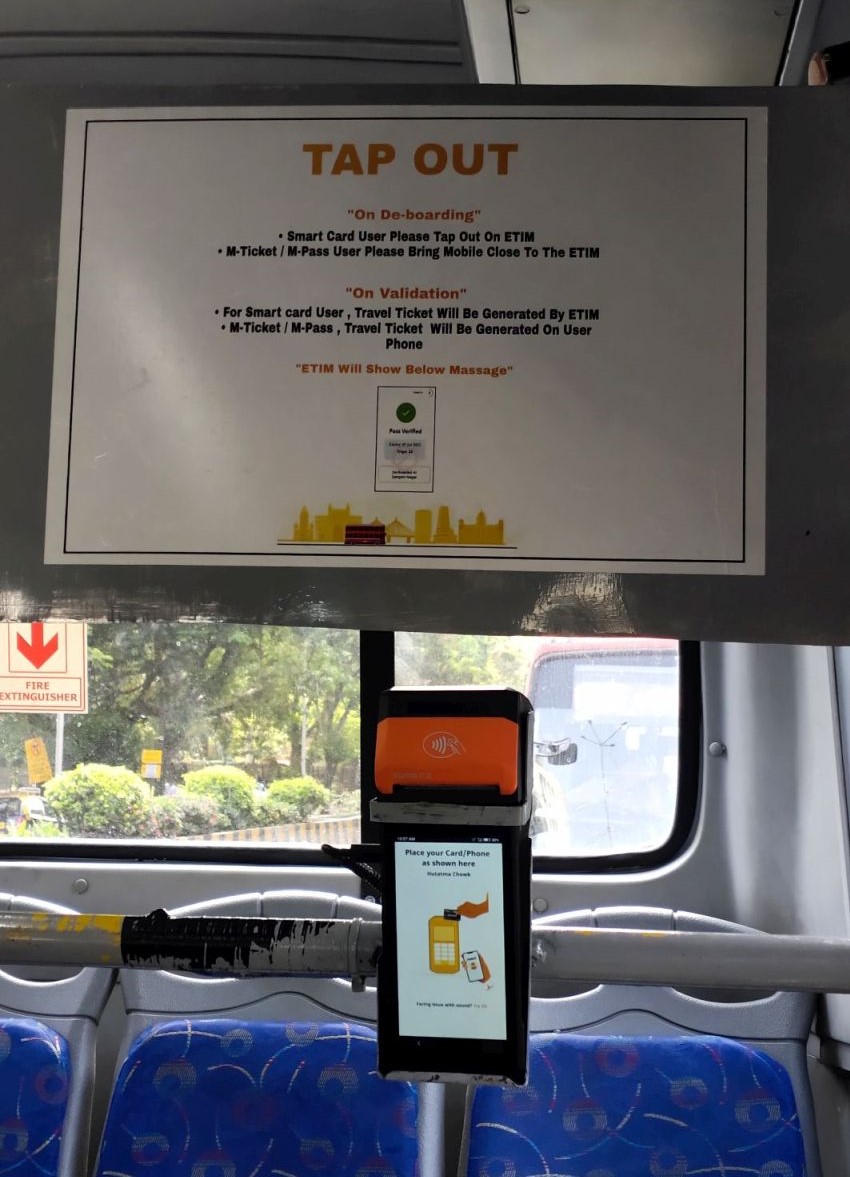

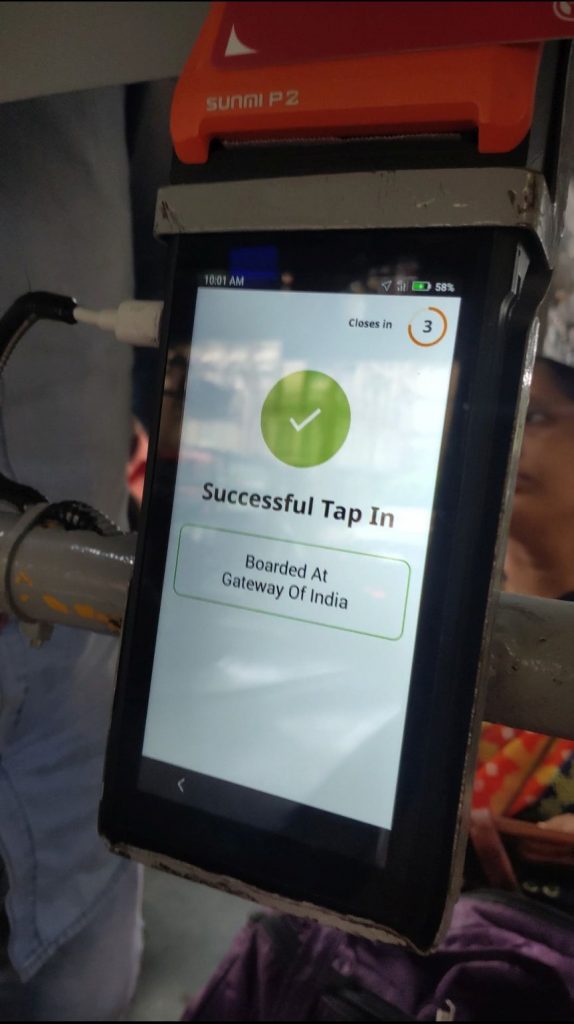

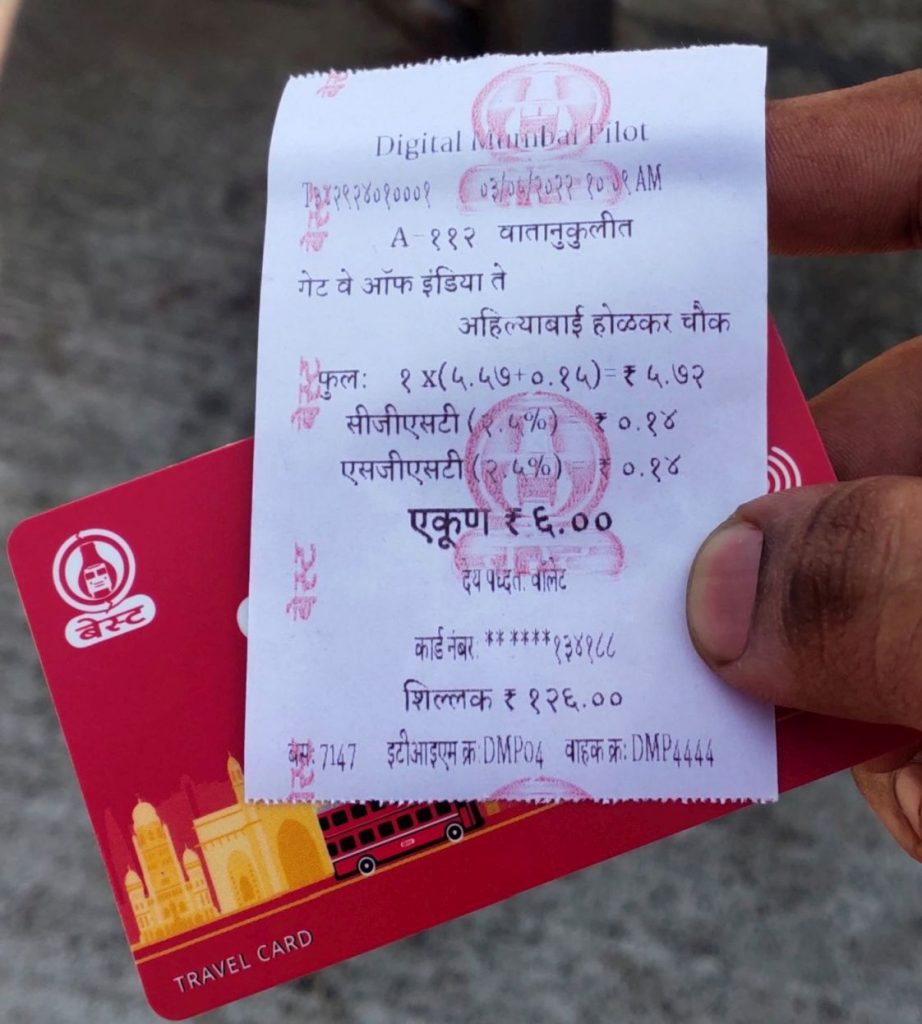

Segment B will cover GUMI across 181 cities. Here, initiatives such as bus priority, multimodal transit, NCMC-based payment systems, and charging infrastructure will be provided.

States, cities and the parastatals will be responsible for making payments to the private operators while the Centre will provide subsidies to the extent provided under the scheme.

This scheme is great news for India as it will impact not just public transport, but a lot of things. For starters, it will give a huge fillip to the manufacturing and the supply-chain ecosystem of buses, their components, and behind-the-meter infrastructure. The increased availability of buses will also change how people perceive commuting and how they actually commute.

One good news that merged right away was Volvo’s entry into the electric bus segment in India. Volvo India stated that it would consider entering the sector under either the Volvo or Eicher brand.

While the government has done a lot in improving the electricity supply system with an increase in renewable energy including solar, wind and even hydel power, it needs to scale up on nuclear power.

Do read this article written by me for Swarajya in 2018: India Needs An Electric-Vehicle Policy; Here’s How It Can Go About It. The government seems to be doing what I had proposed five years ago.

Also, do read Aashish Chandorkar’s article from 2016, on How Indian Cities Can Shift From Diesel To Electric Buses for it explains economies of scale very well.

The shift from the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM, with a jurm of a logo) to the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) to Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid &) Electric Vehicles in India (FAME) to now PM e-Bus Sewa has been quite fantastic.

Featured Image: Image by macrovector on Freepik

![]()